Setting in Stone the Spirit of Public Art

Terrazzo as a medium for art in public places turns a floor into “a destination, where people go just to see it and walk on it,” said artist Joan Henrik. Henrik is the designer and hands-on construction team member for Winds & Currents, one of two award-winning terrazzo floors in the Duluth, MN, Entertainment Convention Center. “A floor can become a focal point in the building, like a sculpture you can walk on,” said Henrik. “Terrazzo as an art form is like a different kind of paintbrush.”

Artist Linda Beaumont has been working with terrazzo on public art projects for over 10 years.

“Terrazzo is a fantastic medium for the built environment, and such a great match for artists working in civic spaces.” Beaumont, of Seattle, explained. “I turn the public space into my studio.”

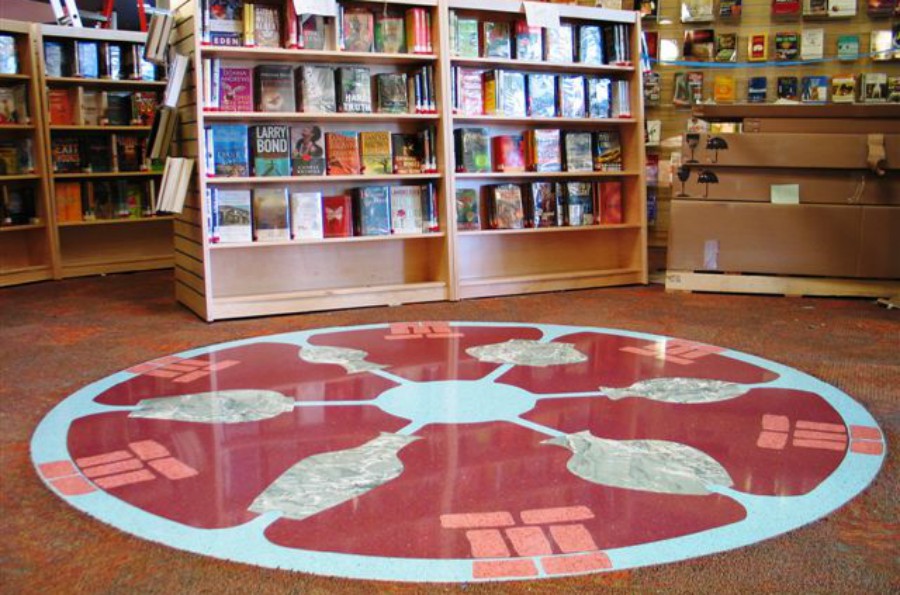

For artist Teresa Cox, currently working on her fifth terrazzo floor and designer of Glacial Twist, another award-winning terrazzo floor in the Duluth Entertainment Convention Center, creating a memorable space is always the goal in designing public places.

“Public art is a chance to recognize the value and power of spaces,” she explained. Even in large spaces, the partnership of terrazzo and public art can create “an intimate, meaningful, beautiful and profound experience,” she said.

Bringing together terrazzo with public art gives the artist the capacity to create spaces distinctive from “anytown USA,” she said, colored by local character and highly accessible to the public.

Not Just for Floors Anymore

Though terrazzo’s reputation was built as a durable, low-maintenance, earth-friendly flooring, its repertory as an artistic medium now extends to actual three-dimensional sculpture.

Beached at the train tracks near the Pacific at Mukilteo Sounder Station in Renton, WA, are two 27-foot-long, solid concrete-core terrazzo earth canoes representing those of the area’s native inhabitants. In one of Beaumont’s projects, the canoes are adorned with seashells, clear and colored glass, semi-precious stones, and mother of pearl.

Pictorial murals also join the list of recent award-winning Art in Public Places projects in terrazzo. In Detroit’s Harmonie Park/Paradise Valley, an outdoor installation of rustic terrazzo, designed by noted muralist Hubert Massey, pays homage to local musicians, historic buildings and public figures. The project also showcases the creative potential and durability of the medium.

“Designing with terrazzo is like painting a picture with stone,” said Massey.

The Epoxy Revolution: Big But Beautiful

“Terrazzo as a medium is compelling as it allows for the creation of strong and custom design in a rich, permanent material,” said Cox. “This complexity and layering of material with the image content appears limitless.”

The muted tones and staid reliability of the 100-year-old terrazzo floors still on the job in courthouses around the country have evolved into a medium of translucency and shadows, depth and dimension in the artist’s hands.

Wending rivers appearing to cascade down stairs in the Winds & Currents design, for example, take texture and shading from hand-cast glass chips in blues, greens and purples.

Greater creativity in the civic environment through today’s terrazzo is one result of what Beaumont calls the “epoxy revolution.” With the same solidity and minimal maintenance of the traditional, more labor-intensive, cement-based terrazzo, epoxy terrazzo has come into its own over the past 15 years. With it have come new generations of varied and vibrant colors and greater design flexibility.

Today’s terrazzo still lasts the lifetime of the building and beyond, yet is now more affordable than its reputation of the past.

“Terrazzo is a thing of beauty and it lasts for ever,” said Beaumont. “It has worth, something you can’t get with carpet.”

LEEDer in Green

Terrazzo can contribute as many as five LEED points for a public art project, based on its durability, low VOC emissions in installation and maintenance, reclaimed and local materials and building reuse.

Originating in 15th-century Italy, terrazzo flooring techniques descended directly from the mosaic artistry of ancient Rome. An early green building system, terrazzo evolved from the resourcefulness of Venetian marble workers as they discovered a creative reuse of discarded stone chips. Terrazzo techniques were introduced to the US in the 1880s by Italian craftsmen.

In keeping with its original premise of resourcefulness and efficiency, terrazzo is still manufactured on the construction site. Marble, stone or glass aggregates, which can often be found locally, are embedded in a cement or epoxy base, filled in and polished.

Tales in Terrazzo

“Paintings can be precious, but public art should meet people half way,” stated Cox.

“The advantage of terrazzo as an artistic medium is that “it can be walked on, spilled on, touched. It’s meant to be experienced,” she explained.

“If it’s a well-designed space, it impacts people,” Cox added. “People can reflect and slow down in a well-designed space.”

Whatever form it takes, art set in terrazzo extends an invitation the public to take pride in the stories, legends and symbols of the locale, its geography and peoples, as told by their artists and craftsmen.

“Terrazzo is almost like 21st century glyphs—objects or images that tell the stories,” Massey noted. He likes knowing that in 100 or 300 years, the terrazzo and its even older natural aggregates will still be around telling the histories he has set down in stone.

“What better medium than something as organic as that?” he asked.

Massey’s artistry in the terrazzo medium lends itself well to the storytelling function of public art. Along with his narrative of Detroit’s history in his Harmonie Park/Paradise Valley mural, the city’s Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History also boasts a terrazzo floor designed by Massey. Etitled “Genealogy” and 72 feet in diameter, the floor recounts the African American experience throughout history.

“If they tore down the building, they’d save the floor, because it has a major function: to tell the history,” Massey declared.

Symbolic Elements

In Cox’s Glacial Twist floor design, large hand-selected, hand-cut local stone aggregates add richness and significance, aesthetically and symbolically, to the imagery.

“The big stones are a visual reminder that it is an organic material,” Cox noted.

Like the terrazzo canoes at Mukiltea Sounder Station, Henrik’s Winds and Currents design also recounts layers and levels of meaning in the community’s geography and heritage.

Henrik’s design alludes to Chippewa traditions through 14 icons embedded in the Winds & Currents floor. Greeting visitors at the entrance to the 3,400-square-foot passageway is the ancient symbol of a welcoming spirit, the red sand hill crane. Another icon recalls the legend of native migration to a turtle-shaped island off the coast of Wisconsin.

Indigenous minerals, including two-foot-high pieces of sculpture in jewelry-grade jasper embedded in the floor, are gleaming acknowledgements of the region’s logging and mining history.

The Spirit of Public Art

This spirit of public art of engaging the community in its own stories is pictured also in the process of creation for artists collaborating with terrazzo and the craft professionals.

“Something happens when we all work together, bringing together the technical skills and the physical process,” said Beaumont.

“It’s different from conceptual, intellectual ideas of art, or having your ego all over, and art in a world all its own,” she noted. “I love it because it isn’t a window to another world, but it’s a piece of the real world. Terrazzo is married to the culture its in. It is, in a real sense, set in stone.”