Innovations in Terrazzo Design

From the sleek, monochromatic appeal of the finest micro-aggregates, terrazzo ranges through a creative spectrum of textures, up through standard aggregate chip sizes, and on to the larger Venetian. It’s at the far end of the range where we find Palladiana terrazzo. Palladiana’s aesthetic can extend from understated to high contrast and assertive, a popular finish that can take on any number of faces.

At its annual national convention in February 2022, the National Terrazzo & Mosaic Association presented Honor Awards to three installations, from among 15 winners, that could be considered innovative variations on the classic Palladiana theme.

Instead of aggregate chips, Palladiana terrazzo showcases the cross-section of considerably heftier, paver-style stones embedded in a cement or epoxy binding material. Traditionally, Palladiana stones generally are irregular shapes and sizes, like rough-hewn tiles, for a hand-crafted aesthetic. Unlike smaller aggregates, which are mixed or sprinkled by hand into the matrix, the slabs are precisely set for more consistent spacing to set off the stones. These award-winning projects took the Palladiana concept in original directions.

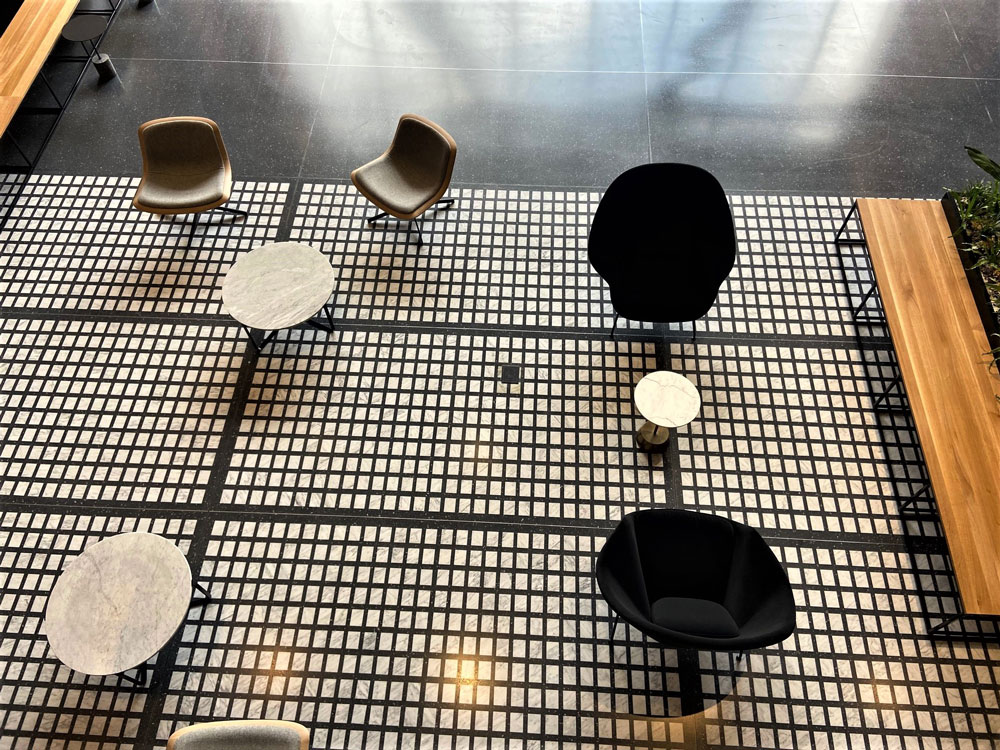

The first award-winning installation is at 800 W. Fulton in Chicago’s Fulton Market neighborhood. Within a mixed-use lobby, the sophisticated terrazzo pattern defines spaces like a series of well-placed area rugs, with considerably lower maintenance demands than carpet. The new LEED-certified construction was recognized with a 2020 Muse Design Award and the 2020 Interior Design Best of Year Award.

To Mesh or Not to Mesh

Fulton

For the project at 800 W. Fulton, the terrazzo artisans cut marble tiles to size with a jig. The designer then hand-selected 12,889 of the 3×5″ inserts, each of which the terrazzo crew set by hand in an 800-square-foot grid, maintaining precise spacing. The inserts are framed by charcoal epoxy terrazzo poured on-site around the tiles.

Fulton

The contractor, Menconi Terrazzo in Bensenville, IL, believed they could save time and control the result of this installation with their system. Not only was a firm date lacking for the marble tiles to be machine-produced, mounted on mesh, and delivered, but mesh also proved too flimsy to control the positioning of such large tiles. Steve Menconi, company president since 1974, said he would use a mesh if working with smaller pieces in varying sizes, which we will see in the next installation.

The Artisan at Essex Crossing

Essex Office

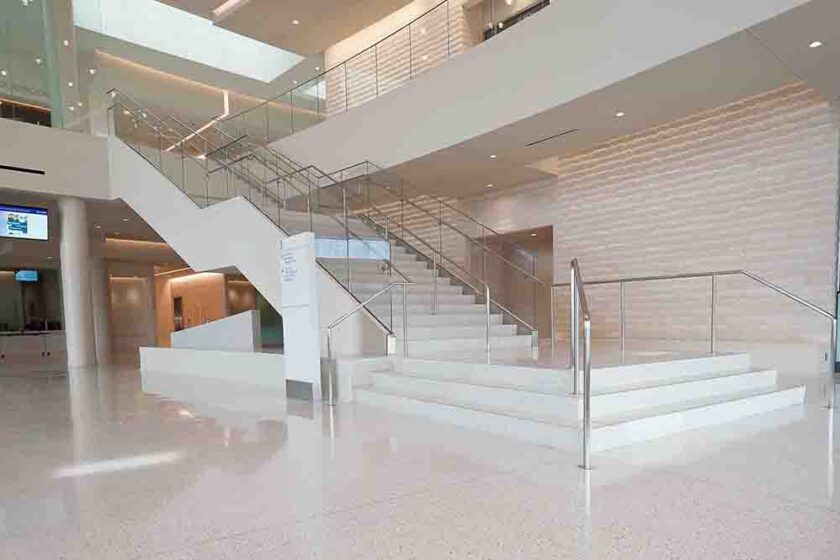

The second project is at Essex Crossing, a 1.65-million-square-foot mixed-use redevelopment project on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The Artisan is a diverse mix of retail spaces undergirding a 19-story affordable housing tower. In an elegant commercial lobby, a subtle precision-cut stone pattern lends texture to the minimalist space. Waterjet-cut Suzuko white marble in alternating rectangles and squares was machine-attached to a mesh for layout. Micro-aggregate epoxy fills the one-inch spacing.

Essex Office

Evan Tarabocchia of Imperial Flooring Systems of Freehold, New Jersey, the contractor on the project, said that using a machine-fabricated mesh backing with the marble pieces attached saved labor costs. The mesh installation with the marble pieces took two to three days; he estimated it would have taken at least twice that long to lay them out by hand. Mr. Tarabocchia, a third-generation terrazzo tradesman, reports that the mesh also made it easier to control the spacing of the marble pieces. He noted that the epoxy has to be poured higher than the pre-polished marble inserts to ensure an even finish after grinding.

Crossing the globe, this new hotel is in the heart of Bucharest, Romania. Instead of larger stones, this innovative use of terrazzo began with a 500-square-foot grid, which the artisans drew by hand, for the precise hand-placement of 8,000 brass rings on the lobby floor.

The architect decided upon the spacing for the brass ring pattern in the lobby the day before the work began, so the contractor had no option but to produce the design by hand. The most painstaking part of the job was drawing the 500-square-foot grid to place the rings perfectly, reported Dan Popovici, owner since 1999 of Aragon in Bucharest, the terrazzo contractor. He said he would have used a mesh if he’d had the time.

Each two-inch-diameter ring was cut from a tube and then set by hand in the floor. Before the epoxy for framing the rings was poured, the tubes were filled with a hard sponge. The sponges were removed, and the darker epoxy mix was hand-troweled into each circle. The reverse pattern in the elevator cabs was precast.

Mr. Popovici calls this design “Yayoi terrazzo” in honor of Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, known for her dotted installations. He intends to produce a series of Yayoi samples for architects showing design options with various sizes and shapes of brass elements.

Our contractors agreed that such installations require careful planning, clear communication with the construction and design team, and extra time.